CASPAR collaboration disassembles accelerator

Experiment is temporarily put in mothballs, but there is still much to do.

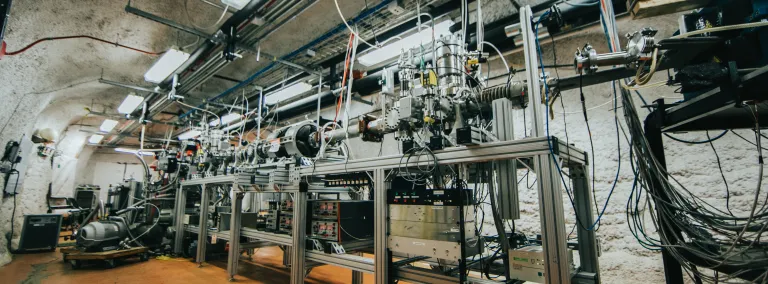

Just over five years ago, members of the CASPAR (Compact Accelerator System for Performing Astrophysical Research) collaboration began installing a 50-foot-long accelerator deep underground on the 4850 Level of Sanford Underground Research Facility. Two years later, in 2017, the accelerator achieved first beam. Since then they’ve been collecting data that could reveal what happens inside the heart of a star as it reaches the end of its life—the time when the elements that make up everything in the universe, including humans, are formed.

“The stellar environment is the cauldron of the cosmos,” said Dan Robertson, an associate professor of physics at Notre Dame. “It’s the place where the elements that make up everything are created. We want to work out where the reactions come from, how the elements were formed and how the materials were deposited to form the Earth.”

CASPAR’s low-energy particle accelerator sent particles racing toward a target, forcing them to interact as they would inside a star. The experiment relied on the nearly one mile of rock above to block cosmic rays that could interfere with the detection of sensitive interactions. However, the walls on either side of the CASPAR cavern won’t block the vibrations from excavation that will begin soon in the area.

In early spring of this year, the CASPAR collaboration began mothballing the experiment, disassembling the accelerator and packing up the equipment. Despite packing up, CASPAR still has much learn.

“It was a long journey getting here—and a complex one,” Robertson said. “It’s a bittersweet moment. We’ve collected a lot of data and we need to analyze that. But for now, we’re going to be in standby mode because we intend to come back in a few years and continue our experiments.”

“The SDSTA is proud to have partnered with the CASPAR Collaboration over these past years of successful data collection,” said Mike Headley, executive director of the South Dakota Science and Technology Authority. “We’re looking forward to the next generation of low-powered accelerator experiment to become a reality deep underground at SURF.”

Although the accelerator has been disassembled and put in storage, “there is still much work to do,” said Frank Strieder, principal investigator for CASPAR and an associate professor of physics at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in Rapid City. “We still have data analysis, publications and Ph.D. theses to develop. And we’re also planning for our return when it is possible.”

Want to learn more? Earlier this year, Mark Hanhardt, experiment support scientist at SURF, gave a virtual tour of the CASPAR experiment space.