Researchers record successful startup of LUX-ZEPLIN dark matter detector at Sanford Underground Research Facility

Press release media

Members of the LUX-ZEPLIN collaboration in the water tank after the outer detector installation.

Photo by Matthew Kapust

LEAD, SD — Deep below the Black Hills of South Dakota in the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF), an innovative and uniquely sensitive dark matter detector – the LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) experiment, led by Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (Berkeley Lab) – has passed a check-out phase of startup operations and delivered first results.

The take home message from this successful startup: “We’re ready and everything’s looking good,” said Berkeley Lab senior physicist and past LZ spokesperson Kevin Lesko. “It’s a complex detector with many parts to it and they are all functioning well within expectations,” he said.

In a paper posted online today on the experiment’s website, LZ researchers report that with the initial run, LZ is already the world’s most sensitive dark matter detector. The paper will appear on the online preprint archive arXiv.org later today. LZ spokesperson Hugh Lippincott of the University of California Santa Barbara said, “We plan to collect about 20 times more data in the coming years, so we’re only getting started. There’s a lot of science to do and it’s very exciting!”

Dark matter particles have never actually been detected – but perhaps not for much longer. The countdown may have started with results from LZ’s first 60 “live days” of testing. These data were collected over a three-and-a-half-month span of initial operations beginning at the end of December. This was a period long enough to confirm that all aspects of the detector were functioning well.

Looking up into the LZ Outer Detector, used to veto radioactivity that can mimic a dark matter signal. Photo by Matthew Kapust

Unseen, because it does not emit, absorb, or scatter light, dark matter’s presence and gravitational pull are nonetheless fundamental to our understanding of the universe. For example, the presence of dark matter, estimated to be about 85 percent of the total mass of the universe, shapes the form and movement of galaxies, and it is invoked by researchers to explain what is known about the large-scale structure and expansion of the universe.

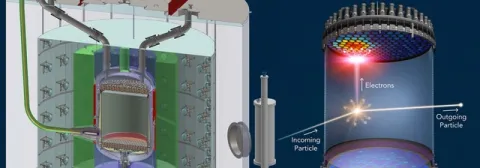

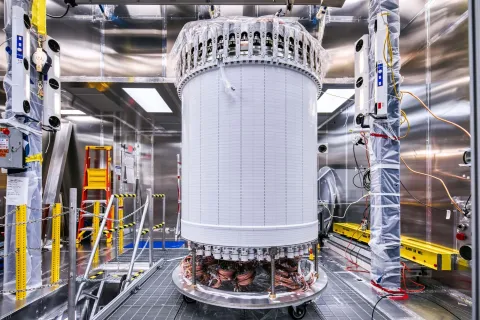

The heart of the LZ dark matter detector is comprised of two nested titanium tanks filled with ten tonnes of very pure liquid xenon and viewed by two arrays of photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) able to detect faint sources of light. The titanium tanks reside in a larger detector system to catch particles that might mimic a dark matter signal.

“I’m thrilled to see this complex detector ready to address the long-standing issue of what dark matter is made of,” said Berkeley Lab Physics Division Director Nathalie Palanque-Delabrouille. “The LZ team now has in hand the most ambitious instrument to do so!”

The design, manufacturing, and installation phases of the LZ detector were led by Berkeley Lab project director Gil Gilchriese in conjunction with an international team of 250 scientists and engineers from over 35 institutions from the US, UK, Portugal, and South Korea. The LZ operations manager is Berkeley Lab’s Simon Fiorucci. Together, the collaboration is hoping to use the instrument to record the first direct evidence of dark matter, the so-called missing mass of the cosmos.

Henrique Araújo, from Imperial College London, leads the UK groups and previously the last phase of the UK-based ZEPLIN-III program. He worked very closely with the Berkeley team and other colleagues to integrate the international contributions. “We started out with two groups with different outlooks and ended up with a highly tuned orchestra working seamlessly together to deliver a great experiment,” Araújo said.

An underground detector

Tucked away about a mile underground at SURF in Lead, S.D., LZ is designed to capture dark matter in the form of weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs). The experiment is underground to protect it from cosmic radiation at the surface that could drown out dark matter signals.

(Left) A schematic of the LZ detector. (Right) Illustration of LZ operation – particles interact in liquid xenon, releasing a flash of light and charge that are collected by photomultiplier tube arrays at top and bottom. (Credit: Left schematic: LZ collaboration. Right image: LZ/SLAC)

Particle collisions in the xenon produce visible scintillation or flashes of light, which are recorded by the PMTs, explained Aaron Manalaysay from Berkeley Lab who, as physics coordinator, led the collaboration’s efforts to produce these first physics results. “The collaboration worked well together to calibrate and to understand the detector response,” Manalaysay said. “Considering we just turned it on a few months ago and during COVID restrictions, it is impressive we have such significant results already.”

The collisions will also knock electrons off xenon atoms, sending them to drift to the top of the chamber under an applied electric field where they produce another flash permitting spatial event reconstruction. The characteristics of the scintillation help determine the types of particles interacting in the xenon.

The South Dakota Science and Technology Authority, which manages SURF through a cooperative agreement with the U.S. Department of Energy, secured 80 percent of the xenon in LZ. Funding came from the South Dakota Governor’s office, the South Dakota Community Foundation, the South Dakota State University Foundation, and the University of South Dakota Foundation.

Mike Headley, executive director of SURF Lab, said, “The entire SURF team congratulates the LZ Collaboration in reaching this major milestone. The LZ team has been a wonderful partner and we’re proud to host them at SURF.”

Fiorucci said the onsite team deserves special praise at this startup milestone, given that the detector was transported underground late in 2019, just before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. He said with travel severely restricted, only a few LZ scientists could make the trip to help on site. The team in South Dakota took excellent care of LZ.

The LZ central detector in the clean room at Sanford Underground Research Facility after assembly, before beginning its journey underground. Photo by Matthew Kapust

“I’d like to second the praise for the team at SURF and would also like to express gratitude to the large number of people who provided remote support throughout the construction, commissioning and operations of LZ, many of whom worked full time from their home institutions making sure the experiment would be a success and continue to do so now,” said Tomasz Biesiadzinski of SLAC, the LZ detector operations manager.

“Lots of subsystems started to come together as we started taking data for detector commissioning, calibrations and science running. Turning on a new experiment is challenging, but we have a great LZ team that worked closely together to get us through the early stages of understanding our detector,” said David Woodward from Pennsylvania State University who coordinates the detector run planning.

Maria Elena Monzani of SLAC, the Deputy Operations Manager for Computing and Software, said “We had amazing scientists and software developers throughout the collaboration, who tirelessly supported data movement, data processing, and simulations, allowing for a flawless commissioning of the detector. The support of NERSC [National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center] was invaluable.”

With confirmation that LZ and its systems are operating successfully, Lesko said, it is time for full-scale observations to begin in hopes that a dark matter particle will collide with a xenon atom in the LZ detector very soon.

The LZ collaboration announced their first results to the scientific community via a public livestream from SURF on July 7. Watch the recorded presentation here.

LZ is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of High Energy Physics and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE Office of Science user facility. LZ is also supported by the Science & Technology Facilities Council of the United Kingdom; the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology; and the Institute for Basic Science, Korea. Over 35 institutions of higher education and advanced research provided support to LZ. The LZ collaboration acknowledges the assistance of the Sanford Underground Research Facility.

Sanford Underground Research Facility is operated by the South Dakota Science and Technology Authority (SDSTA) with funding from the Department of Energy’s Office of Science. Our mission is to advance world class science and inspire learning across generations. Visit SURF at www.sanfordlab.org.

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 14 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab’s facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.