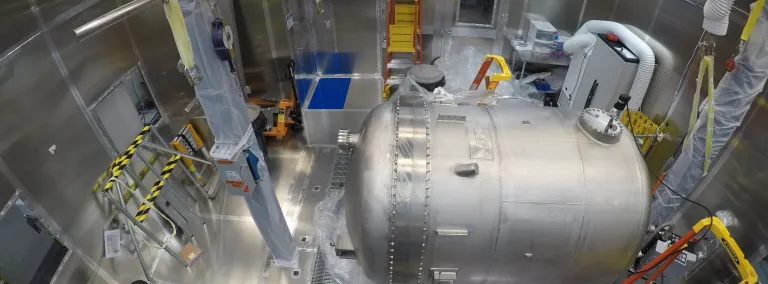

The LZ cryostat undergoes leak tests in the Surface Lab cleanroom.

Matthew KapustDark Matter

Most of the mass of the universe is missing. Where is it and how do we know it exists? Scientists at SURF think WIMPs could be the answer.

Everyone on Earth, and all of the planets, stars and intergalactic gases make up just a fraction—about 5 percent—of all the matter in the universe. So, where’s the rest? Dark energy makes up about 68 percent of the universe; the remaining 27 percent is dark matter. We call it dark matter simply because we don't know what it is and we can't see or touch it.

So, how do we know dark matter exists? We can see its affects on galaxies and clusters of galaxies. Without dark matter, galaxies don't have enough mass to stay together—they would fly apart. There is also indirect evidence that hints at its existence. But scientists underground at Sanford Lab are looking to directly detect dark matter.

Indirect Evidence

We don't know much about dark matter yet, which is a remarkable thing because it makes up 80-85 percent of all the matter in the entire universe. We've never been able to directly detect dark matter in any form, but we know it exists through its effects on the universe, especially through the orbital velocities of stars and gravitational lensing of light around "invisible" objects.

Gravity keeps planets rotating around the sun and the solar system rotating around the galaxy. But when we observe the speed at which galaxies rotate, there simply isn't enough gravity to hold everything together. Think of dark matter as the glue that allows galaxies to generate the extra mass and gravity to keep everything together.

Gravitational lensing occurs as light bends around massive objects such as galaxies, clusters of galaxies and even our own sun. It has been observed for more than a hundred years but becomes especially interesting when observed where there is nothing visible to bend the light.

We don't know much about dark matter yet, which is a remarkable thing because it makes up 80-85% of all the matter in the entire universe.

The Case for WIMPs

Researchers at Sanford Lab believe the leading candidate for a dark matter particle is a WIMP, or Weakly Interacting Massive Particle. If WIMPs exist, billions of them pass through your hand, the Earth and everything on it every second. But because WIMPs interact so weakly with ordinary matter, their ghostly journey goes entirely unnoticed.

Scientists hope that on occasion a WIMP will interact with normal matter through the weak nuclear force. At Sanford Lab, they constructed the LUX dark matter detector and filled it with a third-of-a-ton of cooled super-dense liquid xenon. The xenon is surrounded by powerful sensors designed to detect the tiny flash of light and electrical charge emitted if a WIMP collides with a xenon atom within the tank. The detector’s location at Sanford Lab beneath nearly a mile of rock, and inside a 72,000-gallon, high-purity water tank, helps shield it from cosmic rays and other radiation that would interfere with a dark matter signal.

SURF hosts a highly sensitive WIMP detector beneath nearly a mile of rock, and inside a 72,000-gallon, high-purity water tank, shielding it from cosmic rays and other radiation that would interfere with a dark matter signal.

Turning Xenon into Liquid

Our target is xenon, a colorless, odorless noble gas found in trace amounts in the Earth’s atmosphere. In the search for WIMPs, scientists with LUX and LZ use super dense liquid xenon, which is cooled by liquid nitrogen to -160 Fahrenheit. We use xenon for its ability to emit light and electrons when hit by other particles—a property critical to detecting WIMPs.

The first-generation dark matter detector, LUX, used 350 kilograms of xenon as a target. Now scientists want to go bigger—30 times bigger, in fact. The next generation experiment, called LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ), will hold 10 metric tons of xenon—nearly ¼ of the all xenon produced in an entire year.

Sanford Lab purchased about 80 percent of the xenon needed for LZ. But before it can be used in the experiment, it must be purified. To ensure the xenon is pure enough for the experiment, scientists will run it through the purification process twice. It will take a few years to build LZ but when it's ready the xenon will be ready too.

Liquid Xenon WIMP Detectors

LUX and LZ look for WIMPs in the same way. Each uses a vessel that can hold the liquid xenon. Arrays of photomultiplier tubes, or PMTs, sit above and below the xenon target, where they create an electrical field. Scientists install the detector deep underground to reduce the noise of cosmic rays by a factor of about 10 million. Then they wait, and wait, hoping a WIMP will interact inside the detector.

How will they know they've seen a dark matter particle? Scientists believe that when a WIMP collides with a xenon atom, it creates a flash of light, releasing electrons. The PMTs see that and the electrons are noted by the electrical field. If this happens at the very center of the detector it just might be the signal scientists hope to see.